|

the

earth-mother's

|

|

HOW MY INTEREST IN IRISH SWEATHOUSES STARTED. My discovery of the existence of sweathouses was entirely due to Estyn Evans' Field Guide to Prehistoric and Early Christian Ireland, published in the mid-sixties. He mentioned the Rathlin one (which I never found) and the Tirkane sweathouse near Maghera, co. Derry, which I decided to visit along with the fine portal-tomb at nearby Tirnony. It was in a glen owned by a Miss Dogherty who had serious arthritis

and was getting on in years. She was thrilled that I wanted to see

her sweathouse, and she took me down the slippery slope to show

me it. After that, anytime I was in the area I called in with her.

I brought her the first peach she had ever seen, and she told me

that she had only once seen the sea (at Larne) and was still amazed

by the waves. She was a splendid woman. Later I went to see her

in hospital after a cataract operation (not the outpatient event

it is today), and later again I went to see her after a nephew (I

think) had had her house 'done up' with a grant. Gone was the turf

fire and the cosiness, replaced by a lot of formica. She didn't

like it at all. |

|

IRISH

SWEATHOUSES

Are

Irish sweathouses a continuation of a prehistoric tradition of

inhaling consciousness-altering smoke, recently overlaid or amalgamated

with the prophylactic function of saunas ? Could

the sweating cure possibly be a purifying ritual preceding

psychedelic experience ?

Some have chinks to let out the smoke, but they were necessarily cleared of fire and ash before use - so any chinks (deliberate or otherwise) in the rough construction would have served as ventilation ducts in a cramped space. Where these were too big, they were stopped with sods or with mortar.

Thus they are different from North American sweat-lodges or inipis, which were rarely if ever stone-built, and were heated by carrying hot stones from a nearby fire. Northern European saunas and bath-houses are a modern variant, with an enclosed stove upon or around which stones were placed. Stone retains heat very well.

Cleighran More, county Leitrim: beside a stream

Dowra, county Leitrim.

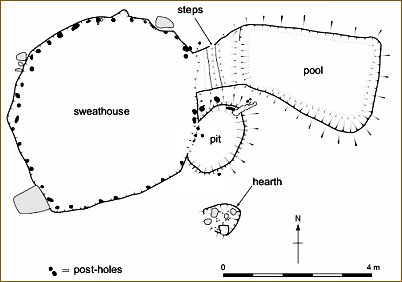

'Small buildings called sweat-houses are erected, somewhat in the shape of a beehive, constructed with stones and turf, neatly put together; the roof being formed of the same material, with a small hole in the centre. There is also an aperture below, just large enough to admit one person, on hands and knees. When required for use, a large fire is lighted in the middle of the floor, and allowed to burn out, by which time the house has become thoroughly heated; the ashes are then swept away, and the patient goes in, having first taken off his clothes, with the exception of his undergarment, which he hands to a friend outside. The hole in the roof is then covered with a flat stone and the entrance is also closed up with sods, to prevent the admission of air. The patient remains within until he begins to perspire copiously, when (if young and strong) he plunges into the sea, but the aged or weak retire to bed for a few hours.' [Gage: A History of the Island of Rathlin, 1851] He also mentions that young women use it for their complexion after burning kelp, and that after about 30 minutes use, their skin is much improved. There is very little mention of sweathouses on the Web, apart from a summary of conclusions from a rescue-dig at Rathpatrick, county Kilkenny - whose author, knowing little about steam baths, saunas, or simple physics (or indeed about the sparse literature on the subject of Irish sweathouses), actually thinks that pouring water on hot stones increases the temperature! This summary suggests that temporary sweathouses of the North American type (made of bent wands and skins or fabric), with a pool, might well have existed in Ireland during the Bronze Age - around 2,500 BCE. The only problem is that the report suggests that stones were heated in a hearth a couple of metres outside the temporary sweathouse, a labour-intensive operation, since it would be easier and safer to erect the structure over the hot stones in a hearth than to roll very hot (presumably rounded) stones down into what amounts to a tent. The author of the summary suggests, however, that they might have been carried on forked sticks. A correspondent from Rhode Island tells me that he and his friends use a shovel - or preferably a pitchfork - to transport glowing stones into the inipi. and that there are reports of deer-antlers also being used. "The stones are commonly the size of a man's head and never gathered from or near a river - because they explode."

The first thing to note is that the present distribution is in the poorest parts of the ignored counties of Ireland: Fermanagh, Leitrim and Cavan, as well as northern Sligo - though 'outliers' have been identified in Wicklow, Cork and Kerry.

Coomura, county Kerry (photo by Aidan Harte)

A typical lime-kiln of NW Cavan - with missing chimney.

Mullan, county Fermanagh

The corbel-roofing goes back, of course, to prehistoric times, and is found in Neolithic tombs all over Europe. It involves the laying of stones in an ever-diminishing coil or spiral until it can be finished with a single stone.

Corbelled shepherd-hut, Artajona (Navarra),

Spain

Legeelan, county Cavan

Doolargy, county Louth (one of several)

Parsons Green, South Tipperary

Parke's Castle, county Sligo

|