SATAN IN THE GROIN

exhibitionist

carvings

on

mediæval churches

male genital exhibitionists on mediæval churches

HIGH-RESOLUTION PHOTOGRAPHS OF MALE AND FEMALE EXHIBITIONISTS

beard-pullers

in the silent orgy

ireland

& the phallic continuum

field

guide

to megalithic ireland

the

earth-mother's

lamentation

beasts and monsters of the mediæval bestiaries

links

to

ENGLISH FEMALE EXHIBITIONISTS ON A FRATERNAL SITE:

Ampney

Saint Peter Gloucestershire

Austerfield

Yorkshire

Bilton in Ainsty Yorkshire

Binstead Isle of Wight

Buckland Buckinghamshire

Copgrove Yorkshire

Cynghordy Carmarthenshire

Donyatt Somerset

Easthorpe Essex

Fiddington Somerset

Holdgate Shropshire

Kilpeck Herefordshire

Llanhamlach Brecon

Llanon Dyfed

Melbourne Derbyshire

Penmon Anglesey

Raglan Castle Monmouthshire

Romsey Hampshire

Royston Hertfordshire

Saintbury Gloucestershire

Stoke-sub-Hamdon Somerset t

Twywell Northamptonshire

Wimborne Dorset

Winterbourne Monckton Wiltshire

Wolston Warwickshire

Map

of most figures in England,

Scotland and Wales

ANOTHER

FRATERNAL SITE FEATURING ENGLISH CHURCHES WITH EXHIBITIONISTS OR RELATED

MOTIFS AND THEIR CONTEXTS

INCLUDES :

Bilton-in-Ainsty

East Yorkshire

Bishop Wilton East Yorkshire

Bugthorpe East Yorkshire

Etton Cambridgeshire

North Grimston North Yorkshire

Nunburnholme East Yorkshire

List

and distribution map

of Irish

exhibitionists

FURTHER READING:

Jones, Malcolm

THE

SECRET MIDDLE AGES: discovering the real medieval world

Stroud,

England:

Sutton Publishing, 2002

(especially

the chapter entitled Wicked Willies with Wings: sex and sexuality in

late medieval art and thought).

It

may be ordered

at a discount through:

and outside

the British Isles through amazon.com

PLUS

MARGINAL

SCULPTURE IN MEDIEVAL FRANCE:

towards the deciphering of an enigmatic pictorial language

Aldershot,

Hants., England:

Scolar Press.

Brookfield, Vermont, USA: Ashgate Publishing Co.

1995

ISBN 1-85928-109-5

This book, however, regards subjects such as exhibitionists and mouth-pullers as marginal - which, being on several doorways and interior capitals, they surely are not.

Wikimedia

slide-show of corbel figures relative to this website

click the right arrow > rather than

the left

photos are of variable quality

"This is excellent stuff. Anthony Weir's the

man when it comes to carvings of this sort. His level-headedness

and his willingness to admit that we don't know

make a refreshing change. That said, I found the witchcraft theory the

most convincing, although I also recognize - like I said - that we don't

know.

Of all the theories I've heard, this, to me, is the one that best explains the facts.

The

Sheela he's carved and buried is something very special, he's a very talented

artist (and stonemason).

That'll confuse the anti-quarians of the future!"

- Tom Morrison

From

Sermons

in Stone

to the Petrified Hag

female figures

- part III:

THE CONUNDRUM ENDURES

Abbeylara (Longford): is this a sheela-na-gig ?

|

The conundrum of sheela-na-gigs in Ireland curiously echoes the enigma of Irish Sweathouses - which may hark back to the same period.

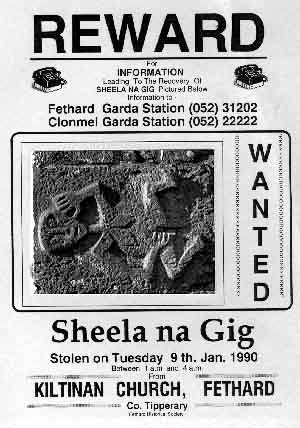

Sweathouse, Killadiskert (Leitrim) Sweathouses are curiously concentrated in the area where counties Leitrim, Cavan and Fermanagh meet, while the sheela-na-gig heartland is the counties of Tipperary and Offaly. Scarcely any more is known about the use of Irish Sweathouses than the meaning(s) or function(s) of sheela-na-gigs. In both instances/phenomena, the peripheral areas of Ireland have hardly any examples. The re-use of exhibitionist figures, sometimes cut or altered to fit another building or another part of a chuch (e.g. Whittlesford and many other insular carvings), echoes the re-use of Mass Dials on churches. These were stone sun-dials (dating from 1100 to the late mediæval period) placed on the south sides of churches to indicate when Mass should be said. Some have been placed - like exhibitionists - the wrong way round or upside-down, and others in porches or other places where the sun cannot reach. The parallel with sheela-na-gigs is significant, and suggests that exhibitionist figures might have been re-used without any particular purpose at all. In Britain, there is a concentration of sheela-na-gigs around the Welsh Marches - but not particularly in Wales. The distribution - of, it must be remembered, surviving examples - does not chime with any of the popular theories of their origins and functions. If some descendant or form of the 'Celtic Hag Goddess', why are there so few in the most 'Celtic' areas of the British Isles ? If they are apotropaic figures to ward off danger and enemies, why are they not on castles of the Welsh Marches, and why are they on so few castles of the western and northern fringes of the Irish Pale, and on no really important strongholds ? The distribution of the Western and Northern Scottish figures suggests an Irish influence - but it could have been the other way round, remembering that the 'Book of Kells' was created on Iona, where there are two female figures and a male, dating from the thirteenth century. Two of the Iona figures are clearly warnings of punishment in Hell for carnal pleasure in this life. Oaksey (Wiltshire) If they were aids to fertility or parturition, why are some so high up as to be almost invisible, and why would they, in any case, be static figures of stone on castles rather than more portable figures ? Female exhibitionists are often cadaverous and look barren rather than fertile. A very good example of a fertility amulet was found in the Rhondda valley in Wales. The belly is obviously pregnant, and the bored hole shows that it was worn round the neck. It is probably not more than 200-250 years old. As I have said earlier, any theory must cover more than 50% of the known figures. The apotropaic theory might be considered to do this - but it is too vague and woolly an idea to be a real explanation. Who exactly would need to be warned off a church or a castle by such means ? People deemed to be evil or a serious threat are usually definable: Protestants, foreigners, English-speakers, Irish-speakers, Welsh-speakers, epileptics, syphilitics, lepers and other 'unclean' beings... In which case, why not phallic carvings associated with virility and uprightness ? Kilpeck (Herefordshire) So the apotropaic theory falls through lack of specificity. Another suggestion is that they are tokens or badges or signs of solidarity - but again one is at a loss to be more specific. Certainly there must be some meta-Christian connection with the Pilgrimage to Santiago, because the routes from England and Ireland (apart from a direct and dangerous sea-crossing to the Asturian coast on the Bay of Biscay) took pilgrims through lands in which Romanesque exhibitionists were a noticeable feature on churches both great and small. The snag with this theory is that while most Romanesque exhibitionists were male, most later ones were female. And it does not explain the insular distribution. One might, however, combine these two theories into the Insurance Theory: they were signs that certain helpers were at hand if the castle or the church were attacked by heresy or plague or a war-lord. In other words, they were like the Fire Insurance plaques which were placed on buildings before municipal Fire Services were set up, to indicate that the owner could pay for the fire to be extinguished. This theory has the merit of diverse application, and it would explain why sheela-na-gigs do not appear on important strongholds (though one is on the important abbey of Holy Cross) - but it does not explain why most of the figures are crudely carved, by non-sculptors.

Ardcath (Meath) If the non-sculptors were men, the figures might be talismanic, or represent some kind of Mystic Bride (or meta-Christian union with Mother Church) in hag- or corpse-disguise. Could the church figures even represent Mother Church ? In which case - what about the Irish castle-figures ? If the virgin-sculptors were women (intactæ or not - or midwives), some magical apotropaic function would be certain. This would not be inconsistent with the building of castles (beneath which the bones of ritually-slaughtered oxen, horses or dogs might be buried, as still occurs for example in certain French vineyards whose viticultors are followers of Rudolf Steiner) but it is hard to see why women - or indeed any non-mason - would be required to carve such figures for a church, unless they were signs that Wise Women - sanctioned by priests - lived locally. On a visit to Bunratty Castle by sheela-na-gig hunter James Clancy, a guide averred that touching the sheela inside the castle enhanced the chances of a woman conceiving. On hearing this, an American turned to his wife and said 'Don't even LOOK at it, Mavis!' Spanish commentators on the Romanesque exhibitionists have put forward the theory of Necesidad Reproductora: the Reconquest of Spain and the Crusades left Western Europe short of males, so lewd carvings were placed on churches in order to excite the passions of the peasants in order to get them to reproduce. This theory takes no account of the larger number of exhibitionist figures in Western France, where there was no population decline. Exciting the passions of the peasantry would merely increase rape and children born out of wedlock: something not encouraged by Mater Ecclesia. But, more obviously, placing auto-fellating males or exhibiting females or copulating couples on the corbel-tables of churches is hardly going to boost the population. Soft porn has not produced a baby-boom, but the general relief at the end of the Second World War did. Moreover, there is slim evidence that the reconquest of Spain resulted in serious depopulation, nor was there any noted in Aquitaine where many exhibitionists of both sexes are found. But the decline of exhibitionist carving after the end of the twelfth century might be related to the establishment during that century (to the horror of the Eastern church) of Confession/Absolution and the certain existence of Purgatory.

There are probably more male than female exhibitionists on Romanesque churches - which could well be because the male anatomy offered more scope for the sculptors. Carvings cost money - a point that most commentators seem to overlook - and were paid for by the yard. They weren't carved (except in extremely poor areas) by local masons or handymen, but by the equivalent of modern jet-setting I.T. specialists who were highly paid, and who, in Spain, often upped and left the churches unfinished, and/or the scaffolding holes unfilled because of some disgruntlement or sheer pressure of demand. These guys were a kind of artisanal élite, and as such, patrons, priests and Benedictine abbots would have been begging, bribing or threatening them to come and carve. So exhibitionists cannot reasonably be seen as merely rustic, philoprogenitive pornography. The keynote of Romanesque figure carving is Iconic Metamorphosis. Motifs morph into other motifs, partly because the motif-bank was not very well controlled by the church, and partly because it is a natural tendency. (Jurgis Baltrušaitis' books on the subject show this admirably.) Pattern-books may not have been very common, and might even have had only rough sketches open to misinterpretation. Sculptors sometimes did not know the significance or symbolism of what they were carving, sometimes they merged two motifs (e.g. drunkenness and licentiousness), and sometimes they simply misinterpreted what they had seen elsewhere. Whittlesford Church (Cambridgeshire) and Kilkea Castle (Kildare) Each of the British islands has one particularly striking exhibitionist group: Whittlesford (ithyphallic bearded male on all fours approaching vulva-pulling female) and Kilkea (ithyphallic boar penetrating a bearded male with helmet and quilted jacket). If the latter - quite astounding - sculpture is indeed, as has been convincingly shown by Dr Peter Harbison, The Temptation of St Anthony, then there is no intrinsic problem in ascribing a meta-Christian religious significance to sheela-na-gigs. In which case something like Mater Ecclesia/Mother Church in some kind of trial or torment (from the Reformation ?) is a possible interpretation, and sheela-na-gigs are - far from being harkings-back to a dubious Great Celtic Hag Goddess (Medbh, Banbha, Morrigán, etc.) - obscure expressions of Catholic piety. Certainly there is considerable circumstantial evidence for sheela-na-gigs being Christian objects - to wit, their presence on churches dating from the eleventh to the sixteenth centuries. There is no evidence whatever either for the 'paganist' viewpoint which dates (like so much of British and Irish 'tradition') from the death-of-God, post-Romantic, latter half of the 19th century, or for a 'folkloric' interpretation beyond the vaguely apotropaic. Nevertheless, it should be borne in mind that English churchyards were used for many more events than burials right up to the end of the mediæval period. What the Church of Rome could not discourage, 'England's Saddam Hussain' - King Henry VIII - and his successors, as heads of the Church of England, could stamp out at will.

Aghagower (Mayo) - photographed before it was stolen. In all cases the question remains: why are there so few sheela-na-gigs elsewhere in NW Europe (though one has been reported at the German North Sea port of Marienhafe, and one in Holland) ? And again, particularly with respect to the remarkable male figure at Painswick in Gloucestershire, why are there so few post-Romanesque male exhibitionists, when males outnumber females on 12th century churches ? And why are so few churches and even fewer castles adorned with these grotesque figures, if they had a 'folk' function ? Until 2007 I had thought that there were no post-Romanesque exhibitionists in France apart from one at Cleyrac (which might even be Romanesque, though it doesn't look it), and a pair at Saint-Antonin-Noble-Val on a 16th century window. However, my colleague Jacques Martin sent me a photograph of a very fine male exhibitionist apparently contemporaneous with the early 14th-century House of the Master of Venery at Cordes-sur-Ciel (Tarn) not far from Saint-Antonin. There may well be more: it is simply a matter of continuing the assiduous search which Jørgen Andersen initiated on the European mainland in the 1970s. In 2025 my friend Florence Merlenghi, who has been pursuing exhibitionists (mainly female) in books and on the Web for many years, pointed me towards the remarkable tongue-sticking masturbator cocking a snook, who is to be found inside the (14th century) anti-Cathar castle of Thouzon in the Vaucluse. An idea half-seriously suggested in my Images of Lust (1986) was that they were a kind of Souvenir Dirty Postcard in Stone, sketched on the Pilgrim Roads, and reproduced on churches and castles. This idea is greatly boosted by the female exhibitionist frieze-carving on a corbel-table of the church at Saint-Vivien, south of Soulac-sur-Mer (Gironde) on the tip of the Garonne Estuary, which was an important point of disembarkation from and re-embarkation to the British Isles. The (Romanesque) St-Vivien exhibitionist is 'classic sheela' even down to the baldness and crudely-indicated rib-cage, and if presented to anyone with a knowledge of the phenomenon would be assumed to be post-Romanesque Irish. Click to see the context of the figure at Saint-Vivien (Gironde) It has been assumed with no evidence at all that the post-Romanesque use of exhibitionist female figures originated in Ireland. But there was only one period in history that anything originated in Ireland and moved East: the early megalithic period, when passage-tombs and large stone circles originated around Sligo, then moved gradually Eastwards. For the rest of history, Ireland has been something of an appendix, colon or rectum of Europe where people, trends and things tend to end up rather than originate. Considering the late Romanesque figures at Whittlesford and Kirknewton, I have a strong feeling (see previous page) that the transformation of Romanesque figures of sin (some of them dancing) to the sheela-na-gig occurred in Britain - where Gig was and maybe still is (in 2026) actually dialectal Northern English for vulva, and the Jig (later gigue in French, with soft G) was a 'lewd' dance originating from thereabouts. Compare also the old word giglot (lewd and wanton woman) and the contemporary gigolo (a posh kind of male-for-female prostitute).

Moreover, not

only does the earliest male

exhibitionist in a Christian context occur on a late 8th (or early

9th) century Anglo-Saxon manuscript, but the earliest depiction

in a Christian context of a damned female suckling (or trying

to remove) an 'unclean' beast throughout eternity is on an Anglo-Saxon

cross-shaft in Lincolnshire. Other questions also spring to mind. Romanesque sculpture was brightly painted like Greek and Roman sculpture and probably all sculpture before the effeminate and dead hand of the Italian Renaissance sculptors changed the concept of sculpture forever. (Imagine those superb Greek statues of kings and heroes coloured in like a child's colouring-book! Imagine those Satyrs with purple - or red - or green penises and scrota in a contrasting colour!) Were the later sheela-na-gigs also painted ? The Rosnaree Mill figure has been almost obliterated by whitewash, but all evidence of ancient paint would long since have been lost on other carvings apart from a couple of indoor figures (Bunratty Castle, Rattoo Round Tower) which, however, show no traces of paint. Dunnaman Castle (Limerick) It is possible that the post-Romanesque sheelas had (at least originally) something to do with the beginnings of the European 'witch-craze'. The first trial for witchcraft in Europe - of Dame Alice Kyteler - took place in Kilkenny in 1324, less than a century after the last Romanesque churches were built. The case against her was prosecuted by the Bishop of Ossory - the mediæval Irish diocese and pre-Norman lordship (covering parts of counties Kilkenny, Tipperary and Offaly or Queen's County) currently containing nearly a quarter of Irish sheela-na-gigs. The case was a cause célèbre involving at different stages the burghers of Kilkenny, the parliament in Dublin and Edward III in London. Bishop Ledrede managed to browbeat the Irish parliament and seized Alice Kyteler's and her family's land and money. She was tried and found guilty, then managed to escape to London, leaving behind her personal servant to be burned in her stead. Edward III subsequently excommunicated the bishop and persuaded the pope in Avignon to confirm his action. Ledrede continued to fulminate against witchcraft, which he claimed the Irish were practising wholesale. Female witches were, of course, always accused of having sex with the devil: a favourite mediæval Christian fantasy alongwith drinking (baptised) babies' blood. Similar ridiculous and appalling calumnies were hurled at Cathars and other heterodox Christians, Templars and Jews.

Redwood Castle (Tipperary) Compare with an undatable rock carving in Galicia :

Moura Pena Furada (Coirós, La Coruña), from Wikipedia.

Moreover, a majority of Irish figures are on the same (south) walls of buildings as the main doorways, suggesting that they were meant to be seen by visitors rather than by malevolent spirits. (For an essay on a remarkable mediæval Italian exhibitionist mural which, surprisingly, seems to be connected both with power-politics and the propaganda of witchcraft, click here.)

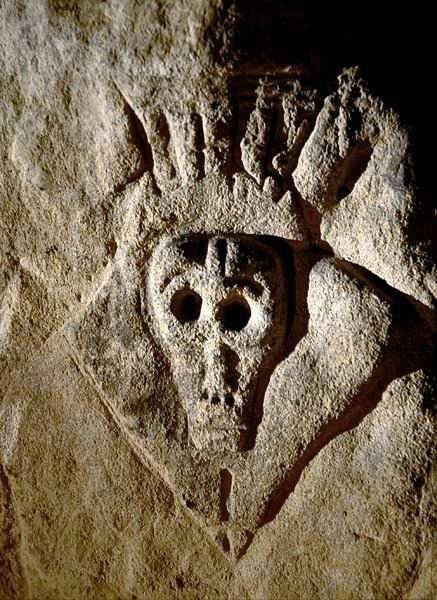

The almost childish figure with characteristic

ribs below the quasi-testicular breasts at In one figure, however, there is a highly significant detail. The low-relief quoin-carving at Balleen Little (Kilkenny) has a rope around its neck and dangling down the left side of its torso - suggestive of a ritual hanging. In his excellent and charming booklet "Sheela na gig" (a discussion of the Fethard and Kiltinan(e) figures published in Fethard in 1991) James O'Connor recounts one local tale linking sheela-na-gigs to female collaborators with Oliver Cromwell's forces, and another linking the place-name of Kiltinan(e) to a Father Tynan who hid from Cromwellians. Since puritan Oliver ineluctably gets the blame for the excesses of Tudor Thomas in both Britain and Ireland, there may just be a connection between sheelas and Henry VIII. Could the witch-motif have been conveniently adapted to represent Anne Boleyn, for example, the first 'heretic' queen of England ? A few of the later exhibitionists are in poses suggestive of dancing, e.g. a jig, notably the Kiltinane church figure near which was recorded the first sheela-na-gig, (or possibly thingumajig). This harks back to the earlier (Romanesque) denunciations in stone of dance, tumbling and other public entertainments. As mentioned above, there is a certain connection between the English figures and the Hundred Years' War fought in the 13th and 14th centuries over a large area of Aquitaine, where dozens of exhibitionists survive, including the remarkably well-carved and well-preserved corbel-carving below, which survives from an abbey almost certainly seen by the English, and sacked in the 16th century by Protestants during the Wars of Religion. Saint-Antonin-Noble-Val (Tarn-et-Garonne)

Yet another small window of speculation is opened by the fact that almost all exhibitionists lack pubic hair. This was on the one hand a sign of the upper-class whore, and on the other a fashion in courtly circles - rather like the perverse shaving of armpits, legs (and faces of men) is in European society generally today. And why did the famous 16th century Swiss doctor Paracelsus prescribe (and illustrate) the engraving of a female exhibitionist upon one of his magical tokens for the cure of gout ? Did Langland's Lady Meede, a complicated female embodying luxury and mundane reward in his widely-circulated Piers the Plowman (written during the 100 years' war) feed into the folklore behind the English figures and those on English castles in Ireland ? Questions and suggestions could multiply like dragons' teeth or modern gadgets. (Another red herring is the Gnostic "Fallen Sophia", the Wisdom-that-is-God who ended up as a whore on the streets of Tyre.) The sad fact is that there is no theory that explains sheela-na-gigs convincingly - and, without startling new evidence from a hitherto unsuspected source, any future books claiming to interpret them will be exercises in futility. And just as candles can also be dildoes, so any one sheela-na-gig could have had a double or even triple significance. When, in 1975, I suggested the title THE WITCH ON THE WALL (London, Allen and Unwin 1977) to Jørgen Andersen for his groundbreaking study of the sheela-na-gig phenomenon (the first scholarly work on the subject now long out of print but sometimes available expensively through abebooks.com), I had no inkling that the castle figures might indeed plausibly be witches...or, for that matter, could even be meaningless kitsch borrowings like the huge fake-stone birds that adorn the gateposts of modern Irish bungalows...

There is no doubt, however, that the female exhibitionist image was some kind of inspiration to visitors and pilgrims travelling in Aquitaine, especially the area between Poitiers and the Pyrenees. The fact that some post-Romanesque insular carvings are very close copies of Romanesque carvings in such places as Saint-Vivien (Gironde), suggests that the latter were sketched by pilgrims/travellers (some of them at least being in holy orders) and later carved by British and Irish sculptors of greater and lesser talent, probably for apotropaic purposes on churches and (in Ireland) on castles. In the latter case, they were possibly a symbol of prestige. This view is enhanced by the unearthing in a Birmingham garden in 2006 of a modern (probably mid-twentieth century) copy, just 27 cms high, of the Kilpeck female exhibitionist. This repeats also the burying of "sheela-na-gigs" in the past, especially in Ireland.

Yet another

explanation, less fanciful than it might seem at first, and able

to account for both the Romanesque and most post-Romanesque figures,

is an anthropological one. Even today, masons and sculptors form exclusive teams and (like many co-operative tradesmen who feel undervalued) perform scabrous rites. In Romanesque times, to be a sculptor was as prestigious as being an international architect today. It is possible that sculptors were more powerful than priests on the ground, because they could simply take off from a site and find employment elsewhere without difficulty. So the carving at Girona (below) might have a different meaning than that which I advanced earlier in Images of Lust. The bishop may well not be overseeing the sculptors like some kind of art commissar, but merely skulking. The sculptors or masons take prominence in the scene, which might be telling us not that nothing went up on a church without ecclesiastical approval, but that what was sculpted went up on a church despite ecclesiastical qualms. So, in this theory, sculptors who met with the artistic approval of their fellows, had the privilege of carving one or more startling corbel - a kind of satire on the exhibition-piece which is required of skilled craftsmen in wood and stone even today, which then was either slipped past ecclesiastical approval or was placed defiantly or by right and rite. Some (very few) might have had to be placed very high or out of sight to avoid local trouble. But it is pertinent to this theory that many churches in Spain were not properly finished: unfilled scaffolding-holes abound, so teams of masons could up and off with an impunity very similar to the propensity for strike action enjoyed by trades unionists in post-War France and Britain. The drawback of this hypothesis is that some Romanesque and most post-Romanesque female exhibitionists are extremely crude efforts. So perhaps a combination of factors can account globally for the Romanesque and post-Romanesque figures: the "dirty postcard" and the initiation-, prentice- or master-piece of a sculptor fully received into his team, guild or confraternity. Cloister capital, Girona (Spain) click to enlarge

Hecklington (Lincolnshire) click to see the whole carving Visible only through binoculars (which of course did not exist in the 15th century), this remarkable carving is neither apotropaic (the woman is being sexually assaulted by a devil, not performing 'a lewd act' of her own volition) nor didactic (since it is hard to make out in detail, hence unlikely to be any kind of warning to the average parisioner or passer-by).

The mystery of the sheelas is more sociological than magical. Though some post-Romanesque ones (especially those on towers and by doorways) are likely to be apotropaic survivals from ancient times, the phenomenon was something of a fashion or craze not dissimilar to the Tulip Fever which much later hit the Netherlands - or as Double Glazing has done recently in the British Isles. Whether or not there were numerous wooden examples, some recall the Anglo-Saxon weoh. Even those which resemble "dirty postcards" from the Pilgrimage Santiago de Compostela - a journey made by hundreds of thousands from the British Isles alone - they were almost certainly put up at different places for different reasons, and those reasons were very likely local or particular, as with this powerful (and relatively recent ?) carving in the catacombs of Paris.

Considering the general lack of exhibitionists in the southern and eastern French Midi, Christina Weising sensibly points out that motifs considered in this website – notably tongue-stickers, anal & genital exhibitionists – are likely to have had different functions or significance in different regions.

There are obviously many historical, religious, regional, art-historical, anthropological and pornographic strands in the skein of the exhibitionist motif, any, many or all of which could have fed into mediæval iconography. As to the vogue that they peculiarly enjoyed in the lowlands of the British Isles during the later Middle Ages, we may never know the several reasons, and must remain content with a kaleidoscopically-informed ignorance in this as in many aspects of social history.

North Porch, Hereford Cathedral

Roof-beam carving, North Burlingham, Norfolk

|

LIST

of PHOTOGRAPHS of MALE and FEMALE EXHIBITIONISTS

on this site, outside this text

with distribution map.

The pictures and text on these pages are condensed (and then expanded)

from a former Work in Progress: 'The Silent Orgy'.

This web-site is dedicated

to the late Martha Weir,

who was amazed but unfazed by these carvings,

and without whom "Images

of Lust"

would never have been researched or written.

List

and distribution-map of Irish

exhibitionists

Map

of most figures in England,

Scotland and Wales

See

also:

and

Another Irish Sheela-na-gig Website >

ESSENTIAL READING

FURTHER READING

Sheela-na-gigs

- Unravelling an Enigma

(a book

with a vehemently-argued but very thin thesis,

illustrated

with 2 line-drawings and 16 fairly poor photographs)

by Barbara

Freitag

click

for cover illustration - of the sheela at Llandrindod Wells

Routledge (London), September 2004

ISBN:

0 41534552 9

Price: UK£22.50

•••

Lifting the Veil:

A New Study of the Sheela-Na-Gigs of Britain and Ireland

by Theresa

C. Oakley

British Archaeological Reports - British Series, 2010

ISBN:

1407305891

Price: UK£48.00

•••

• Short bibliography on sheelanagig.org>

______________

•

SEE ALSO

![]() H.D.

Sankalia:

H.D.

Sankalia:

"The

Nude Goddess or 'Shameless Woman' in Western Asia,

India and South-eastern Asia"

in Artibus Asiæ XIX,

pp. 111-123

Lynn Meskell:

"Goddesses,

Gimbutas and 'New Age' archaeology"

in Antiquity

69 (1995), pp. 74-86

(a fine critique of pseudo-feminist para-archæology)

|

A

very modern interpretation

of the Female Exhibitionist Motif >

An antique (probably Roman) brothel-token.

I am especially grateful to Tina

Negus, Julianna

Lees, Jacques

Martin,

Kjartan Hauglid, Bob

Trubshaw and John

Harding

for their generous help and donation of photos to this website.

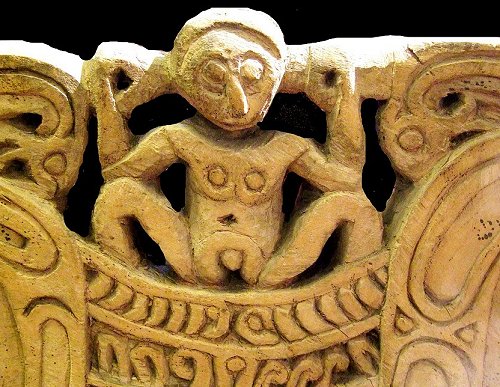

Figure from New Guinea, on display at the Museum of Anthropology

and Archaeology,York,

photographed by Tina Negus.

this figure

at the top left of these pages ![]() was carved

by the author and then buried

was carved

by the author and then buried

This

site has been enhanced by FloatBox

click for another view

click for another view